การฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ุชาวเขมร

การฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ุชาวเขมร (เขมร: ហាយនភាពខ្មែរ หรือ ការប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ខ្មែរ, ฝรั่งเศส: Génocide cambodgien) ถูกดำเนินโดยเขมรแดงภายใต้การนำโดยพล พต ผู้ผลักดันกัมพูชาอย่างรุนแรงต่อลัทธิคอมมิวนิสต์ ส่งผลทำให้มีผู้เสียชีวิต 1.5–2 ล้านคน ตั้งแต่ ค.ศ. 1975 ถึง ค.ศ. 1979 ซึ่งเป็นจำนวนเกือบหนึ่งในสี่ของประชากรชาวกัมพูชาใน ค.ศ. 1975 (ประมาณ 7.8 ล้านคน)[1][2][3]

| การฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ุชาวเขมร | |

|---|---|

| เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของ สงครามเย็นในทวีปเอเชียและการปกครองกัมพูชาของเขมรแดง | |

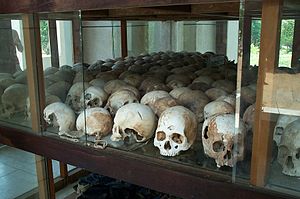

กะโหลกของเหยื่อจากการฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ุชาวเขมรที่อนุสรณ์เจิงเอก | |

| สถานที่ | กัมพูชาประชาธิปไตย |

| วันที่ | 17 เมษายน ค.ศ. 1975 – 7 มกราคม ค.ศ. 1979 (3 ปี, 8 เดือน, 20 วัน) |

| เป้าหมาย | ผู้นำทางทหารและทางการเมืองของสาธารณรัฐเขมรในช่วงเมื่อก่อนหน้า, ผู้นำธุรกิจ, นักเขียน, นักแสดง, แพทย์, นักกฎหมาย, ชาวพุทธ, ชาวจาม, ชาวกัมพูชาเชื้อสายจีน, ชาวคริสต์, ปัญญาชน, ชาวกัมพูชาเชื้อสายไทย, ชาวกัมพูชาเชื้อสายเวียดนาม |

| ประเภท | พันธุฆาต, การสังหารชนชั้น, การสังหารการเมือง, การล้างชาติพันธุ์, วิสามัญฆาตกรรม, การทรมาน, ความอดอยาก, การบังคับใช้แรงงาน, การทดลองกับมนุษย์, การบังคับบุคคลให้สูญหาย, การเนรเทศ, อาชญากรรมต่อมนุษยชาติ |

| ตาย | 1.5 ถึง 2 ล้านคน[1] |

| ผู้ก่อเหตุ | เขมรแดง |

| เหตุจูงใจ | ต่อต้านศาสนาพุทธ, ความรู้สึกต่อต้านชาวจาม, ลัทธิชนชั้น, ต่อต้านศาสนาคริสต์, ต่อต้านปัญญาชน, ความรู้สึกต่อต้านชาวไทย, ความรู้สึกต่อต้านชาวเวียดนาม, อาการกลัวอิสลาม, ลัทธิชาตินิยมเขมรอย่างรุนแรง, อาการกลัวจีน, ลัทธิมากซ์-เลนิน, ลัทธิเหมา |

พล พต และเขมรแดงได้รับการสนับสนุนจากพรรคคอมมิวนิสต์จีน (CPC) และเหมา เจ๋อตง มาช้านาน[4][5][6][7][8][9] มีการคาดการณ์ว่าอย่างน้อย 90 เปอร์เซ็นต์ของความช่วยเหลือจากต่างประเทศแก่เขมรแดงมาจากจีน โดยใน ค.ศ. 1975 มีเพียงอย่างเดียวที่แสดงให้เห็นว่าจำนวนเงินอย่างน้อย 1 ล้านดอลลาร์สหรัฐในความช่วยเหลือด้านเศรษฐกิจและการทหารจากจีนโดยปลอดดอกเบี้ย[9][10][11] ภายหลังจากได้ยึดอำนาจในเดือนเมษายน ค.ศ. 1975 เขมรแดงต้องการที่จะเปลี่ยนประเทศให้กลายเป็นสาธารณรัฐเกษตรกรรมสังคมนิยม ซึ่งก่อตั้งขึ้นตามนโยบายลัทธิเหมาอย่างรุนแรงและได้รับอิทธิพลมาจากการปฏิวัติทางวัฒนธรรม[12][13][14][15] พล พต และเจ้าหน้าที่เขมรแดงคนอื่น ๆ ได้เข้าพบกับประธานเหมาอย่างเป็นทางการที่กรุงปักกิ่ง เมื่อเดือนมิถุนายน ค.ศ. 1975 ซึ่งได้รับการอนุมัติและคำแนะนำ ในขณะที่เจ้าหน้าที่ระดับสูงของพรรรคคอมมิวนิสต์จีน เช่น จาง ชุนเฉียว ได้เดินทางมาเยือนกัมพูชาในภายหลังเพื่อให้ความช่วยเหลือ[16] เพื่อบรรลุเป้าหมายดังกล่าว เขมรแดงได้ทำให้เมืองว่างเปล่าและบังคับให้ชาวกัมพูชาย้ายไปตั้งค่ายแรงงานในชนบทที่มีการประหารชีวิตหมู่ การเกณฑ์บังคับใช้แรงงาน การทำร้ายร่างกาย ความอดอยากหิวโหย และเกิดโรคระบาด[17][18] พวกเขาเริ่มต้นด้วย "maha lout ploh" ซึ่งเป็นการลอกเลียนแบบนโยบายการก้าวกระโดดไกลไปข้างหน้าของจีนที่ก่อให้เกิดการเสียชีวิตกว่าสิบล้านคนในทุพภิกขภัยจีนใหญ่[19][20] ใน ค.ศ. 1976 เขมรแดงได้เปลี่ยนประเทศเป็นกัมพูชาประชาธิปไตย

ในเดือนมกราคม ค.ศ. 1979 ประชากรจำนวน 1.5 ถึง 2 ล้านคน เสียชีวิตเนื่องจากนโยบายของเขมรแดง รวมทั้งชาวกัมพูชาเชื้อสายจีนจำนวน 200,000-300,000 คน ชาวมุสลิม 90,000 คน และชาวกัมพูชาเชื้อสายเวียดนาม 20,000 คน[21][22] ชายเขมรเสียชีวิต 33.5 เปอร์เซ็นต์ และหญิงเขมรเสียชีวิต 15.7 เปอร์เซ็นต์ เมื่อเทียบกับจำนวนประชากร ค.ศ. 1975[3] มีประชากร 20,000 คนได้เข้าคุกเรือนจำความมั่นคงที่ 21, หนึ่งในเรือนจำ 196 แห่งที่เขมรดำเนินการ[3][23] และมีเพียงผู้ใหญ่เจ็ดคนเท่านั้นที่รอดชีวิต[24] นักโทษจะถูกนำตัวไปที่ทุ่งสังหาร ซึ่งพวกเขาจะถูกประหารชีวิต (ซึ่งมักจะใช้ด้วยอีเต้อ เพื่อเป็นการประหยัดกระสุน[25]) และถูกฝังไว้ในหลุมศพหมู่ มีการลักพาตัวและปลูกฝังความคิดต่อเด็กซึ่งเป็นที่แพร่หลาย และมีหลายคนถูกชักนำหรือถูกบังคับให้ก่อกระทำทารุณกรรม[26] ใน ค.ศ. 2009 ศูนย์รวบรวมเอกสารแห่งกัมพูชา (The Documentation Center of Cambodia, DC-Cam) ได้ทำแผนที่หลุมฝังศพหมู่จำนวน 23,745 หลุม ซึ่งมีจำนวนประมาณ 1.3 ล้านคนของเหยื่อที่ต้องสงสัยว่าถูกประหารชีวิต โดยเชื่อกันว่าการประหารชีวิตโดยตรงนั้นมีสัดส่วนถึง 60 เปอร์เซ็นต์ ของจำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตทั้งหมดของการฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ุ[27] กับเหยื่อรายอื่น ๆ ที่ประสบความอดอยากหิวโหย หรือป่วยด้วยโรคระบาด

การฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธุ์ครั้งนี้ก่อให้เกิดการรั่วไหลครั้งที่สองของผู้ลี้ภัย ซึ่งหลายคนได้หลบหนีไปยังประเทศเพื่อนบ้านอย่างเวียดนาม และรองลงมาคือไทย[28] การบุกครองกัมพูชาของเวียดนามถือเป็นจุดสิ้นสุดลงของการฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ด้วยความปราชัยของเขมรแดง ในเดือนมกราคม ค.ศ. 1979[29] เมื่อวันที่ 2 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2001 รัฐบาลกัมพูชาได้จัดตั้งศาลคดีเขมรแดงเพื่อพิจารณาคดีต่อสมาชิกผู้นำเขมรแดงที่มีส่วนรับผิดชอบต่อการฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ชาวเขมร การพิจารณาคดีได้เริ่มต้นขึ้นในวันที่ 17 กุมภาพันธ์ ค.ศ. 2009[30] เมื่อวันที่ 7 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 2014 นวน เจีย และเขียว สัมพัน ถูกศาลตัดสินว่ามีความผิดและถูกจำคุกตลอดชีวิตด้วยข้อหาอาชญากรรมต่อมนุษยชาติในช่วงการฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธุ์[31]

อ้างอิง

แก้- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality Crises: The Case of Cambodia, 1970–1979". Forced Migration and Mortality. National Academies Press. pp. 102–105. ISBN 9780309073349.

As best as can now be estimated, over two million Cambodians died during the 1970s because of the political events of the decade, the vast majority of them during the mere four years of the 'Khmer Rouge' regime. This number of deaths is even more staggering when related to the size of the Cambodian population, then less than eight million. ... Subsequent reevaluations of the demographic data situated the death toll for the [civil war] in the order of 300,000 or less.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (2003). "The Demography of Genocide in Southeast Asia: The Death Tolls in Cambodia, 1975–79, and East Timor, 1975–80". Critical Asian Studies. 35 (4): 585–597. doi:10.1080/1467271032000147041.

We may safely conclude, from known pre- and post-genocide population figures and from professional demographic calculations, that the 1975-79 death toll was between 1.671 and 1.871 million people, 21 to 24 percent of Cambodia's 1975 population.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Locard, Henri (March 2005). "State Violence in Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979) and Retribution (1979–2004)". European Review of History. 12 (1): 121–143. doi:10.1080/13507480500047811.

Between 17 April 1975 and 7 January 1979 the death toll was about 25% of a population of some 7.8 million; 33.5% of men were massacred or died unnatural deaths as against 15.7% of the women, and 41.9% of the population of Phnom Penh. ... Since 1979, the so-called Pol Pot regime has been equated to Hitler and the Nazis. This is why the word 'genocide' (associated with Nazism) has been used for the first time in a distinctly Communist regime by the invading Vietnamese to distance themselves from a government they had overturned. This 'revisionism' was expressed in several ways. The Khmer Rouge were said to have killed 3.3 million, some 1.3 million more people than they had in fact killed. There was one abominable state prison, S–21, now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. In fact, there were more than 150 on the same model, at least one per district. ... For the United States in particular, denouncing the crimes of the Khmer Rouge was not at the top of their agenda in the early 1980s. Instead, as in the case of Afghanistan, it was still at times vital to counter what was perceived as the expansionist policies of the Soviets. The USA prioritised its budding friendship with the Democratic Republic of China to counter the 'evil' influence of the USSR in Southeast Asia, acting through its client state, revolutionary Vietnam. All the ASEAN countries shared that vision. So it became vital, with the military and financial help of China, to revive and develop armed resistance to the Vietnamese troops, with the resurrected KR at its core. ... [France] was instrumental in forcing the Sihanoukists and the Republicans to form an obscene alliance with its former tormentors, the KR, under the name of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) in 1982. In so doing, the international community officially reintegrated some of the worst perpetrators of crimes against humanity into the world diplomatic sphere...

- ↑ Chandler, David P. (2018-02-02). Brother Number One: A Political Biography Of Pol Pot. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-98161-6.

- ↑ "China's Aid Emboldens Cambodia | YaleGlobal Online". yaleglobal.yale.edu. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2020-12-17. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-26.

- ↑ "The Chinese Communist Party's Relationship with the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s: An Ideological Victory and a Strategic Failure". Wilson Center. 2018-12-13. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-26.

- ↑ Hood, Steven J. (1990). "Beijing's Cambodia Gamble and the Prospects for Peace in Indochina: The Khmer Rouge or Sihanouk?". Asian Survey. 30 (10): 977–991. doi:10.2307/2644784. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2644784.

- ↑ "China-Cambodia Relations". www.rfa.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-26.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Levin, Dan (2015-03-30). "China Is Urged to Confront Its Own History". New York Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-26.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (October 2008). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14299-0.

- ↑ Laura, Southgate (2019-05-08). ASEAN Resistance to Sovereignty Violation: Interests, Balancing and the Role of the Vanguard State. Policy Press. ISBN 978-1-5292-0221-2.

- ↑ "波尔布特:并不遥远的教训" (ภาษาจีน). 炎黄春秋. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2020-06-27. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-23.

- ↑ Jackson, Karl D (1989). Cambodia, 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-691-02541-4.

- ↑ Ervin Staub. The roots of evil: the origins of genocide and other group violence. Cambridge University Press, 1989. p. 202

- ↑ David Chandler & Ben Kiernan, บ.ก. (1983). Revolution and its Aftermath. New Haven.

- ↑ Wang, Youqin. "2016:张春桥幽灵" (PDF). The University of Chicago (ภาษาจีน).

- ↑ Etcheson 2005, p. 119.

- ↑ Heuveline 1998, pp. 49–65.

- ↑ "How Red China Supported the Brutal Khmer Rouge". Vision Times. 2018-01-28. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-26.

- ↑ Chandler, David (2018-05-04). A History of Cambodia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-96406-0.

- ↑ Philip Spencer (2012). Genocide Since 1945. p. 69. ISBN 9780415606349.

- ↑ "华侨忆红色高棉屠杀:有文化的华人必死". history.people.com.cn (ภาษาจีน). 2014-04-25. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2020-11-24. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-27.

- ↑ "Mapping the Killing Fields". Documentation Center of Cambodia. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2016-03-26. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2018-06-06.

Through interviews and physical exploration, DC-Cam identified 19,733 mass burial pits, 196 prisons that operated during the Democratic Kampuchea (DK) period, and 81 memorials constructed by survivors of the DK regime.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (2014). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79. Yale University Press. p. 464. ISBN 9780300142990.

Like all but seven of the twenty thousand Tuol Sleng prisoners, she was murdered anyway.

- ↑ Landsiedel, Peter, "The Killing Fields: Genocide in Cambodia", ‘’P&E World Tour’’, 27 March 2017. Accessed 17 March 2019

- ↑ Southerland, D (2006-07-20). "Cambodia Diary 6: Child Soldiers — Driven by Fear and Hate". สืบค้นเมื่อ 2018-03-28.

- ↑ Seybolt, Aronson & Fischoff 2013, p. 238.

- ↑ State of the World's Refugees, 2000 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, p. 92; accessed 21 January 2019

- ↑ Mayersan 2013, p. 182.

- ↑ Mendes 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ "Judgement in Case 002/01 to be pronounced on 7 August 2014 | Drupal". www.eccc.gov.kh. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2019-11-29.