อิหร่านซาฟาวิด

อิหร่านซาฟาวิด หรือ เปอร์เซียซาฟาวิด เรียกอีกอย่างว่า จักรวรรดิซาฟาวิด (เปอร์เซีย: شاهنشاهی صفوی Šāhanšāhi-ye Safavi) เป็นหนึ่งในจักรวรรดิอิหร่านที่ใหญ่และดำรงอยู่นานที่สุดหลังการพิชิตจักรวรรดิเปอร์เซียของมุสลิมในคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 7 ปกครองโดยราชวงศ์ซาฟาวิดใน ค.ศ. 1501 ถึง 1736[25][26][27][28] ส่วนใหญ่ถือเป็นจัดเริ่มต้นของประวัติศาสตร์อิหร่านสมัยใหม่[29] เช่นเดียวกันกับหนึ่งในจักรวรรดิดินปืน[30] อีสมออีลที่ 1 ชาฮ์ซาฟาวิด สถาปนาชีอะฮ์นิกายสิบสองอิมามเป็นศาสนาประจำจักรวรรดิ ถือเป็นหนึ่งในจุดเปลี่ยนที่สำคัญที่สุดในประวัติศาสตร์อิสลาม[31]

ดินแดนอิหร่านอันไพศาล ملک وسیعالفضای ایران รัฐอิหร่าน مملکت ایران ดินแดนที่ได้รับการคุ้มกันของอิหร่าน ممالک محروسهٔ ایران | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1501–1736 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| สถานะ | จักรวรรดิ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| เมืองหลวง | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ภาษาทั่วไป | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ศาสนา | ชีอะฮ์สิบสองอิมาม (ราชการ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| การปกครอง | ราชาธิปไตย | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ชาฮันชาฮ์ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1501–1524 | อีสมออีลที่ 1 (องค์แรก) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1732–1736 | แอบบอสที่ 3 (องค์สุดท้าย) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| แกรนด์วิเซียร์ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1501–1507 | Amir Zakariya (คนแรก) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1729–1736 | Nader Qoli Beg (คนสุดท้าย) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| สภานิติบัญญัติ | สภาแห่งรัฐ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ยุคประวัติศาสตร์ | สมัยใหม่ตอนต้น | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• สถาปนาคณะซาฟาวิดโดยแซฟี-แอด-ดีน แอร์แดบีลี | 1301 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• ก่อตั้ง | 22 ธันวาคม[2] 1501 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• การรุกรานของโฮตัก | 1722 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• การพิชิตอีกครั้งโดยนอเดร์ชอฮ์ | 1726–1729 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• สิ้นสุด | 8 มีนาคม 1736 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• นอเดร์ชอฮ์สวมมงกุฎ | 8 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 1736[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| พื้นที่ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ค.ศ. 1630[4] | 2,900,000 ตารางกิโลเมตร (1,100,000 ตารางไมล์) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ประชากร | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1650[5] | 8–10 ล้านคน | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| สกุลเงิน | Tuman, Abbasi (รวม Abazi), Shahi[6]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

a ศาสนาประจำชาติ[7]

b ภาษาราชการ,[8] เหรียญกษาปณ์,[9][10] การบริหารราชการพลเรือน,[11] ราชสำนัก (เมื่อเอสแฟฮอนกลายเป็นเมืองหลวง),[12] วรรณกรรม,[9][11][13] วาทกรรมเทววิทยา,[9] จดหมายโต้ตอบทางการทูต, ประวัติศาสตร์,[14] สำนักทางศาสนา,[15] กวี[16] c ราชสำนัก,[17][18][19] บุคคลสำคัญทางศาสนา, ทหาร,[14][20][21][22] ภาษาแม่,[14] กวี[14] d ราชสำนัก[23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

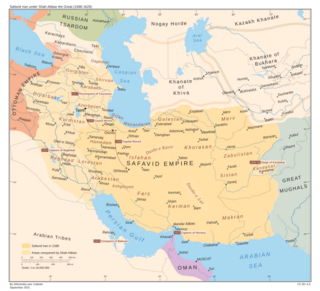

ฝ่ายซาฟาวิดปกครองในช่วง ค.ศ. 1501 ถึง 1722 (ฟื้นฟูในช่วง ค.ศ. 1729 ถึง 1736 และ ค.ศ. 1750 ถึง 1773) และในช่วงสูงสุดสามารถควบคุมพื้นที่ที่ปัจจุบันคืออิหร่าน อาเซอร์ไบจาน บาห์เรน อาร์มีเนีย จอร์เจียตะวันออก ส่วนหนึ่งของคอเคซัสเหนือ อิรัก คูเวต และอัฟกานิสถาน เช่นเดียวกันกับพื้นที่ส่วนหนึ่งของตุรกี ซีเรีย ปากีสถาน เติร์กเมนิสถาน และอุซเบกิสถาน

แม้ว่าจักรวรรดินี้ล่มสลายใน ค.ศ. 1736 มรดกที่ทิ้งไว้คือการฟื้นฟูอิหร่านในฐานะฐานที่มั่นทางเศรษฐกิจระหว่างโลกตะวันออกกับโลกตะวันตก การสถาปนารัฐและระบบข้าราชการประจำที่มีประสิทธิภาพ ซึ่งอิงตาม"การตรวจสอบและถ่วงดุล" นวัตกรรมทางสถาปัตยกรรม และการอุปถัมภ์ศิลปกรรม[29] ซาฟาวิดยังทิ้งร่องรอยจนถึงปัจจุบันด้วยการสถาปนาชีอะฮ์สิบสองอิมามเป็นศาสนาประจำชาติอิหร่าน เช่นเดียวกันกับการขยายอิสลามนิกายชีอะฮ์ไปยังพื้นที่ตะวันออกกลาง เอเชียกลาง คอเคซัส อานาโตเลีย อ่าวเปอร์เซีย และเมโสโปเตเมีย[29][31]

อ้างอิง

แก้- ↑ "... the Order of the Lion and the Sun, a device which, since the 17 century at least, appeared on the national flag of the Safavids the lion representing 'Ali and the sun the glory of the Shiʻi faith", Mikhail Borisovich Piotrovskiĭ, J. M. Rogers, Hermitage Rooms at Somerset House, Courtauld Institute of Art, Heaven on earth: Art from Islamic Lands: Works from the State Hermitage Museum and the Khalili Collection, Prestel, 2004, p. 178.

- ↑ Ghereghlou, Kioumars (October–December 2017). "Chronicling a Dynasty on the Make: New Light on the Early Ṣafavids in Ḥayātī Tabrīzī's Tārīkh (961/1554)". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 137 (4): 827. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.137.4.0805 – โดยทาง Columbia Academic Commons.

Shah Ismāʿīl's enthronement took place in Tabrīz immediately after the battle of Sharūr, on 1 Jumādā II 907/22 December 1501.

- ↑ Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran (Greenwood Press, 2001) p. 95

- ↑ Bang, Peter Fibiger; Bayly, C. A.; Scheidel, Walter (2020). The Oxford World History of Empire: Volume One: The Imperial Experience (ภาษาอังกฤษ). Oxford University Press. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-0-19-977311-4.

- ↑ Blake, Stephen P., ed. (2013), "Safavid, Mughal, and Ottoman Empires", Time in Early Modern Islam: Calendar, Ceremony, and Chronology in the Safavid, Mughal and Ottoman Empires, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–47, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139343305.004, ISBN 978-1-107-03023-7, retrieved 2021-11-10

- ↑ Ferrier, RW, A Journey to Persia: Jean Chardin's Portrait of a Seventeenth-century Empire, p. ix.

- ↑ The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Ed. Cyril Glassé, (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 449.

- ↑ Roemer, H. R. (1986). "The Safavid Period". The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 189–350. ISBN 0-521-20094-6, p. 331: "Depressing though the condition in the country may have been at the time of the fall of Safavids, they cannot be allowed to overshadow the achievements of the dynasty, which was in many respects to prove essential factors in the development of Persia in modern times. These include the maintenance of Persian as the official language and of the present-day boundaries of the country, adherence to the Twelever Shiʻi, the monarchical system, the planning and architectural features of the urban centers, the centralised administration of the state, the alliance of the Shiʻi Ulama with the merchant bazaars, and the symbiosis of the Persian-speaking population with important non-Persian, especially Turkish speaking minorities".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Rudi Matthee, "Safavids เก็บถาวร 2022-09-01 ที่ เวย์แบ็กแมชชีน" in Encyclopædia Iranica, accessed on April 4, 2010. "The Persian focus is also reflected in the fact that theological works also began to be composed in the Persian language and in that Persian verses replaced Arabic on the coins." "The political system that emerged under them had overlapping political and religious boundaries and a core language, Persian, which served as the literary tongue, and even began to replace Arabic as the vehicle for theological discourse".

- ↑ Ronald W Ferrier, The Arts of Persia. Yale University Press. 1989, p. 9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 John R Perry, "Turkic-Iranian contacts", Encyclopædia Iranica, January 24, 2006: "... written Persian, the language of high literature and civil administration, remained virtually unaffected in status and content"

- ↑ Cyril Glassé (ed.), The New Encyclopedia of Islam, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, revised ed., 2003, ISBN 0-7591-0190-6, p. 392: "Shah Abbas moved his capital from Qazvin to Isfahan. His reigned marked the peak of Safavid dynasty's achievement in art, diplomacy, and commerce. It was probably around this time that the court, which originally spoke a Turkic language, began to use Persian"

- ↑ Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History, V, pp. 514–515. Excerpt: "in the heyday of the Mughal, Safawi, and Ottoman regimes New Persian was being patronized as the language of literae humaniores by the ruling element over the whole of this huge realm, while it was also being employed as the official language of administration in those two-thirds of its realm that lay within the Safawi and the Mughal frontiers"

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Mazzaoui, Michel B; Canfield, Robert (2002). "Islamic Culture and Literature in Iran and Central Asia in the early modern period". Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

Safavid power with its distinctive Persian-Shiʻi culture, however, remained a middle ground between its two mighty Turkish neighbors. The Safavid state, which lasted at least until 1722, was essentially a "Turkish" dynasty, with Azeri Turkish (Azerbaijan being the family's home base) as the language of the rulers and the court as well as the Qizilbash military establishment. Shah Ismail wrote poetry in Turkish. The administration nevertheless was Persian, and the Persian language was the vehicle of diplomatic correspondence (insha'), of belles-lettres (adab), and of history (tarikh).

- ↑ Ruda Jurdi Abisaab. "Iran and Pre-Independence Lebanon" in Houchang Esfandiar Chehabi, Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years, IB Tauris 2006, p. 76: "Although the Arabic language was still the medium for religious scholastic expression, it was precisely under the Safavids that hadith complications and doctrinal works of all sorts were being translated to Persian. The ʻAmili (Lebanese scholars of Shiʻi faith) operating through the Court-based religious posts, were forced to master the Persian language; their students translated their instructions into Persian. Persianization went hand in hand with the popularization of 'mainstream' Shiʻi belief."

- ↑ Savory, Roger M.; Karamustafa, Ahmet T. (2012). "ESMĀʿĪL I ṢAFAWĪ: His poetry". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Floor, Willem; Javadi, Hasan (2013). "The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran". Iranian Studies. 46 (4): 569–581. doi:10.1080/00210862.2013.784516. S2CID 161700244.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G.; Sabagh, Georges (1998). The Persian Presence in the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0521591850.

- ↑ Axworthy, Michael (2010). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B. Tauris. p. 33. ISBN 978-0857721938.

- ↑ Roger Savory (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-04251-2.

qizilbash normally spoke Azari brand of Turkish at court, as did the Safavid shahs themselves; lack of familiarity with the Persian language may have contributed to the decline from the pure classical standards of former times

- ↑ Zabiollah Safa (1986), "Persian Literature in the Safavid Period", The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20094-6, pp. 948–965. P. 950: "In day-to-day affairs, the language chiefly used at the Safavid court and by the great military and political officers, as well as the religious dignitaries, was Turkish, not Persian; and the last class of persons wrote their religious works mainly in Arabic. Those who wrote in Persian were either lacking in proper tuition in this tongue, or wrote outside Iran and hence at a distance from centers where Persian was the accepted vernacular, endued with that vitality and susceptibility to skill in its use which a language can have only in places where it truly belongs."

- ↑ Price, Massoume (2005). Iran's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-57607-993-5.

The Shah was a native Turkic speaker and wrote poetry in the Azerbaijani language.

- ↑ Blow 2009, pp. 165–166 "Georgian, Circassian and Armenian were also spoken [at the court], since these were the mother-tongues of many of the ghulams, as well as of a high proportion of the women of the harem. Figueroa heard Abbas speak Georgian, which he had no doubt acquired from his Georgian ghulams and concubines."

- ↑ Flaskerud, Ingvild (2010). Visualizing Belief and Piety in Iranian Shiism. A&C Black. pp. 182–3. ISBN 978-1-4411-4907-7.

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, ed., Iran, a Country study. 1989. University of Michigan, p. 313.

- ↑ Emory C. Bogle. Islam: Origin and Belief. University of Texas Press. 1989, p. 145.

- ↑ Stanford Jay Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. 1977, p. 77.

- ↑ Andrew J. Newman, Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire, IB Tauris (2006).[ต้องการเลขหน้า]

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Matthee, Rudi (2017) [2008]. "Safavid Dynasty". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York: Columbia University. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_509. ISSN 2330-4804. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 May 2022. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 June 2022.

- ↑ Streusand, Douglas E., Islamic Gunpowder Empires: Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals (Boulder, Col : Westview Press, 2011) ("Streusand"), p. 135.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Savory, Roger (2012) [1995]. "Ṣafawids". ใน Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (บ.ก.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 8. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0964. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

บรรณานุกรม

แก้- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0857716767.

- แม่แบบ:The Cambridge History of Iran

- Khanbaghi, Aptin (2006). The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1845110567.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Savory, Roger (2007). Iran under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521042512.

- Sicker, Martin (2001). The Islamic World in Decline: From the Treaty of Karlowitz to the Disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0275968915.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (2001). Encyclopædia Iranica. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0933273566.

อ่านเพิ่ม

แก้- Matthee, Rudi, บ.ก. (2021). The Safavid World. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-94406-0.

- Melville, Charles, บ.ก. (2021). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires. The Idea of Iran, Vol. 10. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-7556-3378-4.

- Christoph Marcinkowski (tr.),Persian Historiography and Geography: Bertold Spuler on Major Works Produced in Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, India and Early Ottoman Turkey, Singapore: Pustaka Nasional, 2003, ISBN 9971-77-488-7.

- Christoph Marcinkowski (tr., ed.),Mirza Rafi‘a's Dastur al-Muluk: A Manual of Later Safavid Administration. Annotated English Translation, Comments on the Offices and Services, and Facsimile of the Unique Persian Manuscript, Kuala Lumpur, ISTAC, 2002, ISBN 983-9379-26-7.

- Christoph Marcinkowski,From Isfahan to Ayutthaya: Contacts between Iran and Siam in the 17th Century, Singapore, Pustaka Nasional, 2005, ISBN 9971-77-491-7.

- "The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors", Adam Olearius, translated by John Davies (1662),

- Hasan Javadi; Willem Floor (2013). "The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran". Iranian Studies. Routledge. 46 (4): 569–581. doi:10.1080/00210862.2013.784516. S2CID 161700244.

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น

แก้- History of the Safavids on Iran Chamber

- "Safavid dynasty", Encyclopædia Iranica by Rudi Matthee

- The History Files: Rulers of Persia

- BBC History of Religion

- Iranian culture and history site

- "Georgians in the Safavid administration", Encyclopædia Iranica

- Artistic and cultural history of the Safavids from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- History of Safavid art

- A Study of the Migration of Shiʻi Works from Arab Regions to Iran at the Early Safavid Era.

- Why is Safavid history important? (Iran Chamber Society)

- Historiography During the Safawid Era

- "Iran ix. Religions in Iran (2) Islam in Iran (2.3) Shiʿism in Iran Since the Safavids: Safavid Period", Encyclopædia Iranica by Hamid Algar